I’m posting my Think Piece from the end of January because I want to post my Think Piece from today but feel I should put them both up, even though I think this one is pandering and not that great. Here it is!

What We Don’t See

It’s my fourth time writing a Think Piece over this book. Currently, I’m thinking about other things. I’m wondering if there’s a way to tie it all in. I’m-a try!

This year is the first year of me being department chair. I wasn’t looking for the position, and I’m not sure about it now, but I’ve been learning a lot through the process—largely about the other side of a lot of issues I didn’t know there was another side to. There are things we, as teachers in a particular department, want, and feel are important; these things simply don’t translate to other areas of the school sometimes, though. And when the school needs to work together as one coherent organism, basically, that’s a problem. A person’s got to figure out how something looks from a few different sides, at least, in order to try to make this coherent functioning work.

Wait for it. I’m getting there.

I had a friend—well, I’ve had several friends, if I’m going to be serious—whose perspectives of a particular event were radically different than mine. I found out, generally in a shocking, revelatory way, that they were right. I mean, maybe I was right too, but in the end, their perspective made sense to me in a way that my original stance no longer did. Did our friendship get stronger because of this? Not often, if I’m gonna be honest. Sometimes revelation isn’t enough. But I learned from it, and I tried to be a better person because of what I gained from learning to see the world—even if only fleetingly, and even then perhaps not totally accurately—from the other person’s perspective. I’m not sure if I actually AM a better person or not, but I tried to let the experience teach me, and I didn’t forget. I try not to forget.

No, I’m still not talking about the book yet. OR AM I. God, this is a terrible Think Piece.

And here’s the biggest thing of late: I’ve been teaching this one book, whose title shall not be named here, for four years. And I finally figured out recently that this big, beautiful book might do more harm than good to some of my students. I don’t want to get into it much here, but some of the things I’ve been realizing about it have made me feel like a big dumb idiot, basically. How could I not see that before? I wonder. What a tremendous blind spot I had no idea I had. I’m not sure how I’m going to deal with the issue, or how I’m going to use what I’ve realized to change my approach, but I know I’m going to be turning it over in my head for a while. How could I not?

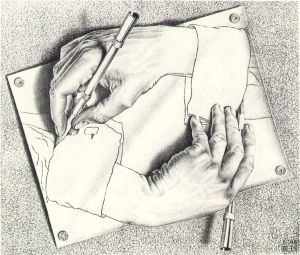

And now I’m going to try to rope this all back into the book. Perspectivism was something Modernists were interested in because they felt it was more true to human experience; it felt more real. And they’re right. If we get frustrated with the narrator of Invisible Man for wearing blinders his whole life, well, are we any different? I’m still discovering—DAILY, and that’s not an exaggeration—my blind spots. There are many. Many, many more blind spots than there are areas of clear vision. I mean, there’s SO MUCH (yes, it needs caps) I don’t know about people, about their experiences, about their perspectives, about their history. So much. I am limited by my own perspective, and yeah, I’m sure I buy into a lot of lies that I ought to know better than to believe, though that’s not really my point here (maybe it should be, as acknowledging this might make us a lot more sympathetic to the narrator).

I used to think this book was about invisibility. It’s a reasonable conclusion! But I think, today, it might be more about blindness—about what we don’t see about each other, about what we CAN’T see, at least not right away. And invisibility is important, it’s maybe the most important thing, but it’s clearly a result of the blindness. When we don’t see people, we make them feel invisible, and we’ve seen, via this narrator, what that does to a person. When we don’t see problems in all their profound multifacetedness (know it’s not a word; don’t care), we don’t come up with workable solutions to them. When we don’t TRY to see beyond our own perspective, we lose friends, we alienate others, we are big dumb idiots. I can’t decide whether our blind spots make us more or less human (didn’t the narrator also struggle with this?), but I think, if anything, Invisible Man is trying to call attention to them.